About This Episode

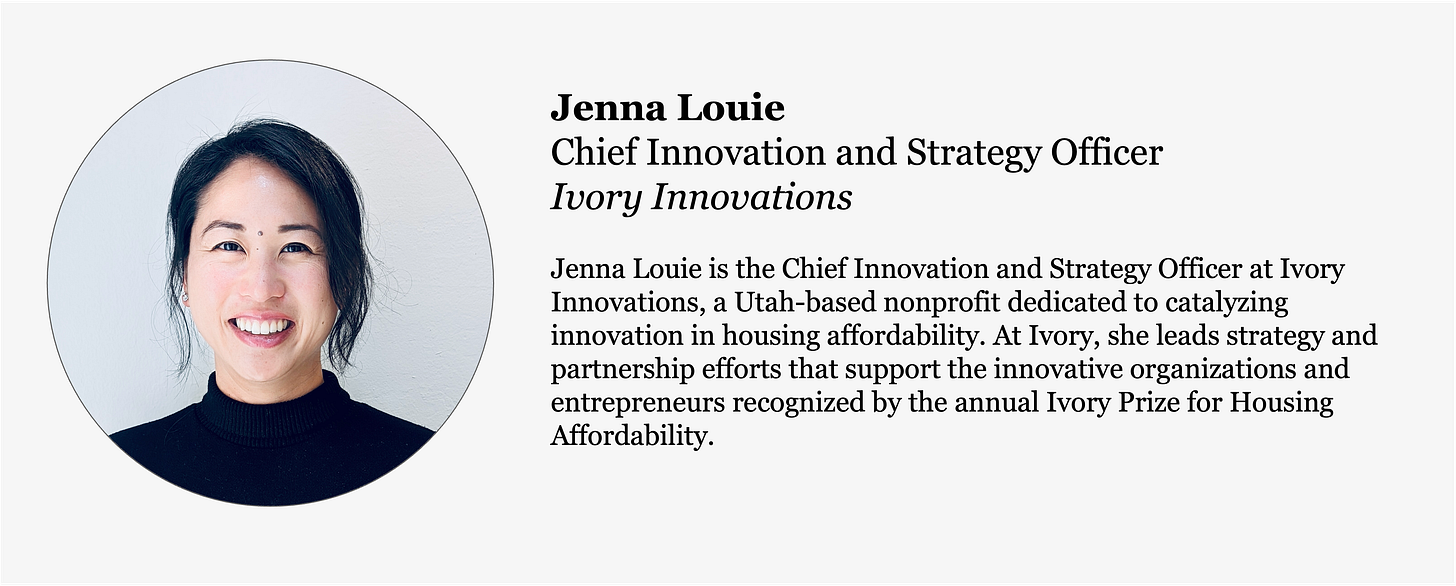

Today’s episode is about housing innovation, or really about the women and the organizations who help support innovation wherever it happens. My guests, Jenna Louie from Ivory Innovations and Michelle Boyd from Terner Labs, work to identify, nurture, support, and build a wide range of innovative approaches to housing. They support new companies, new orgs, new people, new policies and new ideas. They help others help themselves, and roll up their sleeves and build stuff directly.

They also were a ton of fun to talk about housing, and if you like nerds talking about off-site construction, ADU policy, capital, scale, climate and more, and all in under an hour, this is definitely the episode for you. Thanks as always for tuning in, and if you like the show, please give it some love on social media or pass it along to someone who needs to hear Michelle or Jenna or any of my other amazing guests.

This Episode’s Guests

Interview Transcript

Alex Schafran: Jenna Louie, Michelle Boyd. Welcome to Housing After Dark. Really excited to have you both here for a conversation, not just about housing innovation, because I think everyone that has come on this show is an innovator in housing, but in particular, ways to support innovation more broadly or perhaps create a better housing innovation ecosystem or something of that nature. Really excited for this conversation. As is tradition now, we start with each of you as individual humans and your housing histories. So Jenna, let’s start with you. How did you become a houser?

Jenna Louie: I became a houser through a little bit of a circuitous path. When I was 22, I was in my first job after college and I remember it was winter, I was working on the east coast, and it was just bleak. I had been working for about 6 months. It was the first time I had a really professional job, I had spent my summers during college doing these fun research international projects. So I had been working for six months, at a desk job, and thought “Man, is this what I’m going to do for the next 50 years of my life?! This is tough.” And I came up, I’m pretty type A, and I thought, I need to come up with some kind of framework. I need a framework that’s going to help me get through the next 50 years of my career, so I came up with this mantra, which was “I want to lead a career where I can help people better thrive where they live, work and travel.”

And this helped me because it was broad. There’s a lot in there. But it was also specific enough to some of the interests that I knew that I had. Where they live, I was interested in cities and had been interested in housing. Where they work, I was actually working in diversity and inclusion consulting, and so I thought, okay yeah this fits. And where they travel, I had always been interested in the travel industry. I grew up in Hawaii and as most are aware, Hawaii is a pretty small island in the Pacific and if you’re going to go anywhere, you are really getting on a plane for at least five years. From an early age, we went to visit my family on the mainland and so I thought that might be a good place.

So with that mantra in mind, I spent the next couple years of my career bouncing around different jobs. Eventually after a stint in diversity and inclusion consulting and then a stint in the corporate travel industry, I ended up in housing. It was really through business school that I came back to a focus on housing and thinking about how we better support people in the communities where they are locally around the country. Of course the housing affordability crisis has been growing for decades, I would say there has been more recently it has become a crunch that became urgent and something that I wanted to help address. I came to Ivory about three and a half years ago and it’s been a great journey.

Alex Schafran: Fantastic. Michelle, I know that as part of your journey, you also have an MBA. This is a first ever Housing After Dark episode, I believe, with one MBA, let alone two MBAs. There’s more than that I believe.

Michelle Boyd: Yes, I did get an MBA. Jenna and I were actually at school at the same time. Different schools. I was at the better school, Berkeley while Jenna was at Stanford. My interest in housing started when I was really young. I grew up in the Detroit suburbs, and my family is from Detroit going back several generations. A long family history that’s intertwined with a very complex story of Detroit. The neighborhood I lived in was one where people would buy lots and build a house. My dad was very creative, he was trained as an architect. He actually designed our house in a beautiful place facing the woods. Our community was almost entirely white. When I was six the first Black family bought a lot in our neighborhood, built a beautiful custom home. Right before they moved it, it was burnt to the ground. The driveway was actually covered in racial slurs. Talk about the 90s, the spirit of color blindness.

Alex Schafran: This wasn’t 1962.

Michelle Boyd: No, this is the mid 1990s. I remember the glow in the sky from the fire of the house that was a few 100 feet from my parents house. I was very young. I didn't really understand at the time. But several years later, I was at a local event for MLK Day that happened at my high school, and someone asked us to share a story about racism as they experience it, like as a kid experiences it. I raised my hand, I told the story, and the little girl in front of me, black girl flipped her head around (I'm white. I should say that, for folks who don't know me), flipped her head around. Was like, “That's my house.”

And the family had actually rebuilt an incredible place, moved back in and had a little girl who was my age. And so from there, we became friends, and I really formed my understanding of the world at a really young age, to understand that people didn't want this family, my friend, to live in my neighborhood, someone who was wealthy enough to, you know, build and design their own home, couldn't escape this legacy of extreme racism and history within Detroit. Those who've been to Detroit may know that there's a huge difference in how it feels in the city versus the suburbs. Like the physical character is very different. The quality of the physical character is very different.

And so with that story and kind of understanding the world through my dad, who ended up working in real estate, learning through him, it gave me this housing anchor and physical space anchor, and the idea that there are these forces and people that seemed very mysterious to me as a kid, that didn't want, like communities and people to live together. So I originally studied this through thinking, and I've always liked math, so I originally was like, maybe I'll think about, like, government investment and money. I started working at an impact investing advisory firm. I then had a little bit of time to work in nonprofit consulting, and got to take a few steps back and think about urban issues as a whole, I worked at the Bridgespan group and worked on racial equity and urban issues as a whole. It felt like every new project, I always kept coming back to housing. It was always the thing that was most interesting to me.

And then I did one housing project, then I became the housing person, and I loved it. It's always been this issue that brings together all these things I care about: racial equity, thinking about how the intersection of private sector and the government, place, opportunity to think about conversations around sustainability, and as someone who just loves the physical space around me, it seemed as a way to really bring that passion into what I do. I've been here ever since, and I specifically I got really frustrated working on housing and philanthropy, I felt like there just wasn't I had one client tell us who had more money than God, say that he felt like putting money into housing was putting his money in a big black hole that was going to suck all of this money up at $750,000 a door.

I was like, He's not wrong. And so I went back to business school, studied real estate finance with a real focus on trying to figure out how to make better use of the different resources and capital intensive nature of housing and the private sector and government dollars, to think through more creative approaches. And I've been here ever since.

Alex Schafran: Well, I'm excited to talk more about housing finance innovations, and more about the role that innovation plays in racial equity and justice and addressing inequality, because I know that all of these issues, in various ways, are things that have come up in both of your work.

So let's start with Terner Labs. So many of you may be familiar with the Terner Center, then there's also the Terner Labs, your nonprofit partner. Interestingly enough, the Lab is not a research institute. That's the center. Tell us a little bit about the work of Terner Labs, and specifically, in following the theme of today's show, the work that you all do around innovation and housing.

Michelle Boyd: So we founded Terner Labs as the nonprofit spin off affiliate of the Tener Center back in 2020/2021 and our mission has been to support more innovation and scale of innovation within the housing sector. We do this through a few ways. Our primary and first program was to support entrepreneurs and innovators, people with bold ideas that may not have the network or traction or funding or maybe considered too out there (then you don't like institutional support to bring that forward). So we started our Housing Venture Lab program back in 2019 and have since supported four cohorts of innovators. So 22 innovators with wraparound advising support, grants and really helping them think through how they interact with policy and different industry partnerships and bring what may be a small, more sort of an idea up to a broader level of scale. And we work across the whole spectrum, as the Terner Center does, from homeownership to rental housing to solutions for people who are living on the streets to things that are kind of technical and finance-y, to nonprofit community development, to VC backable tech companies.

We've now expanded our sorts of innovators that were launching another program this summer called the Builders Lab that really doubled down (in a similar model), but doubled down to serve the need of innovators within the built environment, specifically around architecture, construction and design. We see a lot of challenges in companies we've supported, companies we've known, companies we've all seen who have really struggled to scale within that sector. And we see a lot of potential to both provide more support for entrepreneurs and help them collectively navigate and change some of the systemic factors that are holding companies back from really stepping in to meet the market need of reducing cost and increasing supply. So that's our innovator support.

We have an area of work where we also think about the capital gap for innovators. This is one where we're emerging. We do some advisory work for impact investment firms and financial institutions. We're working on an impact investment vehicle, actually, with Ivory and some others, so thinking about the capital gap because there's a huge gap in what will actually takes to get something big enough that it could then get state funding or bank funding, and there's huge gap there where I think impact investing can play a role.

Our other primary focus is, we've actually started developing tools ourselves. We saw through the Terner Center a real gap in research and policy tools that can help make policy making and overall research even more evidence based and more efficient. So we have this housing policy simulator that we've been building, both in the City of Los Angeles and now for the City of San Francisco, and six other jurisdictions here in California that we're actually taking into new states in the years to come. We've found it could be really useful for policymakers to actually toggle all these differently induced changes and simulate the potential effect in order to make more evidence based decision making.

So that's the spectrum of what we do. I'd say as we've grown as an organization, we've also done a lot with the folks at Ivory and others, and brought different change makers together to think through how they can support innovation. But I can let Jenna talk about some of that work, because that's a lot of what she does as well.

Alex Schafran: Yeah, so Jenna, give us the basics about Ivory.

Jenna Louie: Michelle, it's so fun to be on this podcast together, because so much of what you mentioned resonates with me and some of the work we're doing, and I think there are so many areas of compliment, even in our innovators work, and how we support up and coming organizations or organizations that have really promising solutions. We share a lot of those groups. But taking a step back. Our mission in Ivory is to catalyze innovation and housing affordability. We have a couple of different pillars underneath that. We were founded back in 2018/2019 by the Ivory family. They own the largest homebuilding company in Utah, and so they're a top 50 builder in the country, but right about 50. That's been just a really interesting kind of origin story for us as an organization. We started with the key pillar of supporting entrepreneurs. We have 147 organizations in our cohort, because we run a prize every year focused on finding the most innovative orgs in three areas, 1) construction and design 2) finance and 3) policy and regulatory reform.

Much like Michelle and the Terner Labs, these can be organizations that are small nonprofits. They can be big for profits with a really innovative program. They can be government entities, you name it, and we hope to provide those same wraparound supports and services, in addition to connection with funding partners, connections with each other, etc. And so that has been a really promising area of work. That's where we started.

We also do a lot of work with student entrepreneurs. When we think about the housing crisis, we think conversations like this are fantastic, and housers and professional people are fantastic. But I'm going to make the assumption that many of us who are listening to the show are also stably housed. And one of the things that we've seen in Utah, and has been really impactful for our work with students, is that many of the kids we work with you know, are the University of Utah, and as the state school Utah has become more unaffordable over the last couple of years, more quickly than anyone had expected. And so some of the interns that we have were capped with a number of hours we can give them for some reasons through the university, and they're also driving for Uber on the side in order to pay their bills. And so when we think about the importance of the next generation in the work we do every year, we sponsor a Hack-A-House, where we invite students to participate and think of new ideas, and dream up new solutions. That’s something that we do that we're really proud of and is also a little bit off the beaten path, I think, for some of the think tank-y research organizations in our space, where we're really trying to bring that next generation in. The third pillar of our support is convening and learning. Whether it's events, whether it's an innovations database, with all of different hundreds of organizations that we've evaluated over time, whether it's an innovative policy database that I'm happy to talk a little bit more about later, trying to share what we're seeing across the country, trying to make that data available and shareable to others who are interested in the space.

The last pillar is something we actually just started two years ago, as we're also a nonprofit developer in the state of Utah, building about 900 units of income restricted housing over the next three years. That’s a really interesting connection with a leading home builder, because we have some of the capabilities as an organization that say your average think tank or research institution wouldn't. Excited to explore all of these areas, it's a lot of different things on a team of about eight so we wear a lot of different hats, but it’s fun.

Alex Schafran: One of the many reasons why I was excited about doing this episode is that I'm a kind of housing maximalist. I want my housing plate to be as full as possible. I want you to challenge me to learn a new part of housing that I don't already know I get. I do a lot of strategic planning, and everybody thinks strategic planning is like narrowing your focus. What I love is that between the two of y'all especially, it's sort of like it's every corner, and it seems to be like you're not afraid to add a new pillar if you need to, or add a new area if you need to. If it's a data question, we can do data. If it's a, actually build the housing, if it's student support, if it's a human question, right? Innovation and how we treat humans and raise humans and housing. Has that been part of y'all's approach to try to stay curious and to keep moving into new areas?

Jenna Louie: It's definitely been a focus for us at Ivory. And I'll really applaud the Ivory family, for their leadership here and in trying to take new approaches. I'd say we have a very strong piloting culture on our team, and so we'll often come up against something of. Who's putting innovation into action when it comes to actual affordability and some of these new ideas. And so we started up the operating foundation where we build these units. We don't have that perfect ecosystem or flywheel yet, right? We still sometimes struggle, even internally. If we have this great sourcing process to find innovators. We have capital and we have units, and yet it's still hard, right? And this is even within a small team, what Michelle's team is building out with the Builders Lab of how do you get capital and more of an accelerator model focus there as opposed to more of a development model to support some of these new innovators, new materials, new methods, is really exciting to us. There is so much room to run in the housing innovation ecosystem space. I would say the water’s warm, come on in. And so very much the housing maximalist approach with a strong piloting focus at Ivory. Michelle, what's that like for you?

Michelle Boyd: I see Terner Labs as a platform where it’s like: where can you take all this industry expertise and policy expertise and really deep research knowledge of the Tener Center and bring that to bear with the innovation culture of Terner Labs to support the place where there's the most need and most opportunity for innovation to advance the conversation around housing.

With our initial program, the Housing Venture Lab, the first part of that was supporting the next generation of leaders with really great ideas. We've supported a really strong focus on diverse leaders. Almost two thirds of our cohort is led by organizations who are led by people of color, with a really strong focus on women, people who may not be in the housing industry, kind of supporting that next crop and helping them get to scale faster.

When we expanded into the construction space, there’s also thinking about construction innovation. It is this place where we need research and policy and business innovation and adaptations and industry practice more or less, all at the same time. And so we see a real opportunity to bring the resources we have to bear and our experience supporting entrepreneurs with this connection to policy and research through the Terner Center to really support that sector as large, and then with the tools, it was also like, well, we have this research and tool building capability, and we've also been helping entrepreneurs for five years now, and there's some of this that we can actually do, and do this ourselves. I don't know if there's a pure business there where we can support the ongoing revenue of this tool purely through people paying for it, because cities and governments can't pay that much for it. And so that's an opportunity where having this nonprofit model that's able to bring in some philanthropy funding and bring in government funding, other support, can really help some of these tools that may not otherwise get started.

None of that quite answers your question. We’re at this point now where we now have these core programs, and we're really focusing on implementation and in honing what we're best at and contributing that. So it might be a little while till we launch a new, new initiative.

Alex Schafran: For me it’s really refreshing, especially being in the Bay Area and being part of Silicon Valley, where so often innovation means either new companies or new tech. And if it's not one or both of those things, it's not innovation, as opposed to just that really holistic approach I think that you all are taking, you know, recognizing policy has innovation in it, and policy is an important part of that ecosystem, leadership, development, the actual human beings, as we talked about earlier. It's super impressive. And I also, again, appreciate just sort of the willingness to dive into difficult spaces. Shout out to Issi Roman at Terner. It’s not called the Terner Dashboard anymore, is it?

Michelle Boyd:Jenna Louie: Housing Policy Simulator.

Alex Schafran: That is a much fancier, nicer word. Or, again, the policy database that Jenna, I'm hoping that you're going to talk about in a sec. It’s really refreshing and I think the I word and innovation can get overused, and I think it's made too many people kind of skeptical of it, and about people who talk about it and are in that ecosystem. Especially for folks whose goal is to address issues in race and racial equity and homelessness, etc. And I think what you're doing is really important in that.

So along these lines, I think now is a really good time where we can sort of talk about some of the very specific spaces. Again, it's such a huge diverse array of spaces that you are both excited about and everybody in the audience should know that people are going to be talking about things that they're working on. I won't charge any of the companies that you mention for this product placement, but product placement is encouraged.

They're welcome to subscribe to the show, and if any of them want to sponsor the show. Housing After Dark is looking for a sponsor. Just saying.

What are the things that get both of you excited? So many of them are your children, so you may not be able to mention all of them. So apologies to those who don't make it. I know that they all still love them.

Jenny, why don't we start with you? What are the things that get you excited? Or one of the things that get you excited? Maybe we can go back and forth.

Jenna Louie: One of the things I am thrilled to mention is that we announced our 2024 Ivory Prize for Housing Affordability winners back in May. You can learn more at ivoryprize.org and I will give a shout out to those organizations, there are four of them across the three categories that we work on.

In policy and regulatory reform, we actually had two winners. Our judges had so much trouble picking that we ended up with a tie. The two organizations, or two entities, are the City of San Diego for their ADU bonus program. And FirstRepair, which I don't know if you all have seen the documentary from PBS called The Big Payback. But FirstRepair is an organization focused on supporting and scaling reparations movements around the country for Black Americans who have been historically disenfranchised, everything about racial equity. I know that many of us are well versed in this, so I won't go into too much detail, but those are two really interesting organizations.

And I'll say as a quick aside is that we have looked so much at ADUs over the last few years, and we see the City of San Diego's bonus program is a really interesting kind of turbocharging of what's happening at a state level in California. What you can do with the bonus program in San Diego is, if you're in a transit priority area, you can have an unlimited number of ADUs, essentially multi-family ADUs, as long as you're doing a one for one affordable and market rate unit. Where previously, you might only be able to put four total units on a lot, if you're in a transit priority area in San Diego, you're actually able to put up to an unlimited number.

I think Gary Geiler, who's running that program in San Diego, mentioned that someone is coming in with 100 because they have a really big lot in a formerly industrial area in San Diego. The lot size supports it, and you're getting 50 infill, affordable ADU units. ADU in air quotes, because really these look like multifamily buildings and 50 market rate units at the same time. So the NIMBYs are very much up in arms. They are not expecting this in their lovely single family suburban neighborhoods, but these are also transit priority areas. How do you find a way to really amp up infill density in a way that is leveraging a lot of the state programs and just taking that a step farther.

Alex Schafran: There is definitely something in the water in the 619. Shout out to the folks down in San Diego. It’s a hotbed of housing innovation. I'm not really sure what's going on. Also, shout out to Muhammad Alameldin who is from Terner (the Center side) who had a really good report on the City of the San Diego ADU program.

Michelle, what's getting you excited? Jenna, we'll come back to you because I know there are more exciting Ivory winners and Ivory spaces. Is there anything that's getting you excited? It doesn't have to be a Terner winner, but it can be.

Michelle Boyd: At the time we are recording this podcast, we haven't picked our cohort for 2024. I may actually take the theme around like policy land use and regulatory reform to talk a little bit about the work we're doing with our simulator. There are a few things that are particularly interesting about that.

One of the things is the amazing traction that we've gotten, and interest that we've gotten, as we've been talking to places outside of California who have been eager. They've kind of waded into land use regulatory reform, really following the California model. But then have also seen that California, you know, passed was, like, 500 bills over five years. We can’t pass that many, Like, how do we know what to do? How do we know if this is worth a political fight, or this is worth a political fight, or if this is actually going to benefit this or that? And there's a real need for more empirical research and studying the impact of various laws in California, and that remains for us on the Center side of the house and with other research institutions.

But the simulator that we built, which has a very rigorous economic reform and tons of data that we vetted that goes into it, does allow you to kind of turn on what happens if you increase floor area ratios by 50% and how does that compare to if you increase density limits by two and model like between these two different policies, which is more likely to produce more housing units over the next 10 years, based on doing the math.

That has been really exciting to start talking to new states and meet people who are really excited for and are basically like, “What do you need? I'm going to write this into my fundraising proposal for the next three years. Let's lock arms and bring this into this new state.” So that's been really exciting to feel the general opportunity and excitement around land use form on a national scale and I know that that's something Jenna may be able to speak to as well.

Alex Schafran: Before Jenna jumps in, I do want to say. I can't emphasize enough how important it is to do this work. We are flying blind so often. So often when states pass legislation that does land use reform, we don't actually know what it will do. And this has been a really long journey. I'll link to an older substack I wrote on civic data infrastructure in housing that talks a little bit about the simulator when it was still known as the dashboard. Shout out to Ian Carlton and Map Craft, speaking of another small, innovative, interesting company that we love, that has been part of this work. But Jenna, I know you want to jump in here. This is an area that you have been working on as well.

Jenna Louie: Yeah, it's true. I just want to also really double down on what we've been saying about how important this is. We've seen states and cities like, you know, Minneapolis or Montana, right? The Montana miracle, passing legislation and just getting caught up in lawsuits, following it. How far can you push forward housing policy when policies can be challenged, policies can be slow. I think that kind of data backed angle, Michelle, of what your team is doing is so valid. It's so important. It reminds me a little bit of the National Zoning Atlas effort to just make zoning clear, understandable, objective, right? There's not really a policy angle there. It's really just showing, you know, here's what zoning looks like across the state, and here's what that means for housing stock. When you have that kind of data, I know that was a really important effort that helped, actually some of the upzoning work that took place in Connecticut, that took place in Montana. That data-backed, evidence-backed measure, I think really matters.

Michelle Boyd: I'm so glad you brought that up. Like we are able to think about new states at the level of speed (which is still slow) because we're able to use National Zoning Atlas data. An investment like that makes the stuff that we are doing more possible. We could collect that data ourselves, but it just slows down the whole process. So I have this centralized database that is available to other researchers. And when we're building in places that don't have NZA data, we're collecting it in a way that helps with that project moving forward, and that level of data infrastructure I'm really excited for what that will make possible in the years ahead as it gets built up.

Alex Schafran: So Jenna. Tell us a little bit more about your policy database, because I think this is a good time for that theme.

Jenna Louie: The policy database that Ivory is launching is a little bit more nascent. We launched in June 2024 and what it's designed to do is actually help burgeoning areas of interest across the housing policy world just become more known.

We started with four different areas of legislation that we've seen as hot topics across the country. So YIGBY (Yes In God’s Backyard) legislation, office to residential conversations, transit oriented development, and social housing. These are the four topics that are the first ones out the gate for us. What we've done is collect model policies from different places across the country. Everyone's like, “Oh yeah, you got to go look at Seattle and what they did for YIGBY. Oh, you've got to go look at this in that place for transit oriented development.”

And we're trying to put that all just into a simple format for housers and others who are interested in these laws to say, “Oh yeah. Here's the kind of collective knowledge that we have around an issue. How can we take those and adapt them for what looks right in our community.” It’s got no data behind it, but it is very much a central gathering place. I guess it's got qualitative data. Let me say that, there's no calculations they're running on the back end, not like the policy simulator, but it's just a gathering place for helping some of those conversations get a little bit off the ground, and to help us centralize some of that knowledge.

Alex Schafran: One of the areas where I think we need a lot of innovation is on how we learn, and it's a hard space to work in because we all learn in very different ways. In housing, it's like, you know, you need learning for the nonprofit sector, you need learning for the public sector, in finance, architecture, in every aspect. The ecosystem of learning and how we are both at initial training and whatever we are in school or on the earliest part of our career, but also all that mid-career learning that you have to keep up with is really hard, and so I applaud this effort.

I know Furman Center in New York is also working on their Housing Solutions Lab and trying to build that out. It's a tough space. I've seen some good efforts. I've seen some efforts that don't quite get off the ground. I'm not sure if we'll ever kind of get it perfect, but I applaud you for wading into that.

Jenna Louie: Yeah, and let me just shout out an invitation. You can visit it on ivoryinnovations.org. And we want your feedback. Again that piloting culture at Ivory, we certainly don't think we're going to get it right at the gate. So tell us what we're doing wrong. Tell us what we're missing. We want to hear from you. Alex, we want to hear from you.

Alex Schafran: So this is actually now the speed round, Michelle and Jenna, where I'm going to ask you about very specific innovations that I know that you're working on, and you can tell me about this.

Michelle, let's start with one of our favorite subjects, off site construction. Now I was going to call it modular, and then allow Michelle to correct me as a demonstration of it, because, you know. Let's talk about offside. This is all of the various things penalized, construction, modular construction, all the various ways that we are working to innovate in building housing, not on the site, but elsewhere, and then bring it to the site.

Michelle Boyd: I'm gonna word you one up and use the word industrialized.

Alex Schafran: That's my new favorite “I” word.

Michelle Boyd: Industrializing portions of the construction process that can happen on site, which is also possible. At Terner Labs, we've supported some companies here and there that work in the industrialized construction space. We worked with Kit Switch, which is here in the Bay Area (which is also an idea that started at an Ivory Prize Hack-A-House). I was actually their judge. Was brought in as a Hack-A-House judge many years ago and then many years later they came to the Housing Lab Accelerator program.

Kit Switch does modularized kitchens, and that can be used in both new construction and retrofit. And then we've also worked with an amazing group Module out of Pittsburgh that does Net Zero construction for townhomes and infill housing. And there's a couple that we're looking at this year, and also some that we've looked at in the past that have taken a design innovation angle. We have seen that work, and then across research at the Terner Center, and also watching a lot of the companies that work up here in the Bay Area that have really struggled to scale. And if we one of the ways I think about it is as a whole sector, like a huge change in industry practice, in an extremely regulated, extremely fragmented industry.

In Silicon Valley, we like to think that, like, oh, one company can start with one product, and they will transform the industry which works for software, but does not work in this context. We've seen these companies get huge investments and then fail, and then the smaller companies trod along but make errors, struggle to get their prices in an appropriate place, have to take on an incredible amount of their first adopters and customers actually got an incredible amount of risk, which a low margin business of housing doesn't really work. We are excited to put forward this new program and think through with them some of the sector wide changes in both policy and industry practice that can actually bring this sector to scale.

Ws we've seen in and Jenna knows this, who got to tour the world as part of these innovative housing, thes tours of more mature sectors in other countries. Other countries have seen really huge movement by the government to start up these industries, either by the government purchasing a bunch of units as a way to provide a pipeline for innovative companies, the government assuming some of the risk through either insurance or risk sharing products, and also standardizing some of the regulatory frameworks that companies that these companies and their customers have to operate under. And that's just the starting list, but those are all things that can happen at the state and also very much at the federal level that I'm really excited to look at. I'm really excited that the Strategic Growth Council here in California is really exploring this. I think there's a lot of opportunities for further ways that we could be moving this forward here in California, but that's something I’m really excited about. We’ll be announcing our first quarter the Builders Lab in the fall will be five companies that are innovating in this space.

Alex Schafran: Well, I promise there will be a Housing After Dark episode only on industrialized and modular and panelized and off site construction. Let me just add to it. I'm also going to add sort of larger projects, the mega projects, which is another subject I've written about as also another kind of key opportunity we have places like the Concord Neville Weapon Station that can produce that consistent, persistent, not cyclical demand over a 20 year period of time. Also happens to have enough land and be next to major industrial sites that can produce some of those boxes, or near our friends at Factory OS and other places we're already doing it.

There are so many solutions, and some of them are in the innovation space, but some of them are not. Boxes and panels can't just sit in the factory the way you can keep your software on your hard drive, wherever you keep it, and then roll it back out when it's ready, but if the market's not ready to absorb it consistently, your company's gonna fall apart. And one little problem, I just had a visit from a veteran of RAD Urban who produced one of the most beautiful buildings in my neighborhood. It's just an amazing building.

I learned that one small mistake took them down. And you know that, just again, the type of thing that is unique to this very difficult and challenging and fascinating corner of innovation.

Michelle Boyd: It's not that unique. I think we can take a lot of stuff out of the playbook of the climate, climate sector and green technology. Just think about the rebate that you get if you, if you're if someone's a homeowner and wants to buy a heat pump, you get $1,500 off it. I think that number is right from the government.

That’s exactly it. If the market can't yet produce a product at the price that people are willing to pay, and so the government steps in to bring down that price. This is industrial policy. It is the government supporting the start of new sectors that are beneficial to our country at large. And there's a lot we can look at from that playbook if we are to decide that this is a place that we think is really important for addressing the joint housing and climate crisis.

Alex Schafran: Okay, Jenna, I'm gonna ask you one quick question, because we're running low on time. I don't know if you can guess the innovation that I'm gonna ask you about. The answer is Montgomery County. So shout out to all my social housers out there, your favorite county housing agency, Montgomery County, Maryland, also won an Ivory prize this year. There will also be another episode of housing at the dark on social housing coming up. I don't exactly know when, but it's coming. So tell us a little bit about y'all thinking about Montgomery County.

Jenna Louie: Montgomery County is our Ivory Prize Finance winner this year. The model that they have with the Housing Production Fund is just really interesting, right? We have seen, as Michelle has mentioned, there's a lot of funding gaps when it comes to construction innovation. How do you implement new building methods? It's also true for just normal buildings, right? How do you get more affordable units online? Especially larger projects that aren't just kind of smaller infill units.

We have ADU innovation taking place, but that doesn't really solve the kind of larger scale building financing challenges. And so what we've seen with the Housing Production Fund is just a new model of county financing, really interesting, really thoughtful ways of putting that money to work.

And so for those who aren't familiar, Montgomery County is in Maryland, right outside of Washington, DC, and they have created $100 million bond backed fund that recycles itself

roughly every seven years and can create, I think, around 3,000 units of housing using that fund.

It’s actually publicly funded developed housing, but it is mixed income from the start, because 30% of the units built using that fund, using Montgomery County's model, will be held as affordable, and 70% will be market rate and used to replenish that fund more quickly.

It’s an alternative to LIHTC that we've been really interested in exploring. We would like to see more places adopt and think creatively about how to fund public housing, how to fund social housing in this way. And so that pushed it over the edge. For our judges, it was a no brainer.

Alex Schafran: It is exciting. I'm also super excited for all the folks who are going to Vienna and going to Singapore and going to all these places to learn about housing finance and housing innovation elsewhere. But it's really exciting that we're starting to be able to pull more from Hawaii or home state from Montgomery County. Maryland, Someday, perhaps Jenna and I will conspire to help Marin County be the Montgomery County of California. That's a subject for another future podcast.

Alex Schafran: Jenna, one quick shout out to the last but not least of the Ivory Prize winners for this past year, Villa. Tell us a little bit about Villa.

Jenna Louie: Yeah, Villa is awesome on the industrialized construction side of things. They are a startup, actually based in the Bay Area, and they're using manufactured housing units to build pocket neighborhoods, really around the country. And so when you think of, how can you take infill development just a step farther from a building perspective, using manufactured housing units and actually creating town story developments us in manufactured housing units, and actually creating townhouse developments and townhomes that are really interesting, cottages, pocket neighborhoods that bring a different sort of infill into communities where that's really needed.

From a building perspective, again, you know, infinitely scalable, because those types of units are regulated at the federal level, rather than at the local level, as is true for on site or even state level like off site or industrialized construction units. And so thrilled that they are our final winner.

Alex Schafran: I want to talk as a final thing. Give me one area that for you is a real challenge in your innovation work, and one area where you have some hope and excitement for the future. We'll start with you, Jenna.

Jenna Louie: An area for the future that I am really interested in is actually something that's happening in Utah right now. There's a new bill that's winding its way through the legislature, I believe, and just through the channels of government, but it's essentially creating a state finance vehicle, a state finance vehicle for subsidizing starter homes.

And so Governor Cox has announced that he would like to support the creation or the development of 35,000 starter homes across the state. And one of the things that they are doing is taking, I believe, about a billion dollars of the state surplus fund that sits and putting that to work in low cost financing for developers.

So let's say you're a developer out in the Utah suburbs, and you are going to build 100 homes in a master plan community. If you agree to set the sale price of those homes below a certain threshold that's been established as a “starter home price”, you can access funding and low cost debt financing from the government, from this fund to make that happen. It's a different way of thinking about how we put money to work in order to incentivize things that builders want, right? I need low cost financing and things that the state wants. I need to find a way to not build these houses myself, but to get developers on board to do this. They’re still working out how exactly it's going to happen, but I'm pretty sure it will move forward.

You hear about all of this innovation happening on the coasts, right? We think Montgomery county, everything in California, New York is doing cool things. But Utah, I would say, is a sleeper state for some of these things, and I think there's just a lot of energy in the state for what we're doing. And that's a small example.

Alex Schfran: Michelle, how about for you? One challenge that we see a lot with our innovators, and this is speaking, it's true in the construction space, but speaking a lot from our housing Venture Lab alumni, is the capital gap. I spoke to this a little bit earlier, but that there's a really charismatic and visionary founder may be able to raise a certain amount of money from philanthropy to, like, pilot an idea, or from one or two people to pilot an idea, prove it out, and think through a new way of acquiring a neighborhood, acquiring homes, to give an example.

They may get a lot of traction from that, but then it's not quite enough traction to go to a bank or go to the government to then say, “Hey, can you fund this model?” Then they can try to go back to philanthropy. But usually philanthropy can't write a big enough check for them to then test it out, because they have to spread their grants at a certain amount across their different priorities. They can't get bank debt, or even necessarily even work with the CDFI landscape, who has to either have much bigger loans or bigger cap, bigger investments than this company could absorb, or has they have to look more like other stuff they funded in the past so that they can underwrite their risk appropriately and understand how to price their financing. And they definitely can't go to more traditional banks that exist at a much larger scale.

We see a lot of our founders try to pitch to venture capital, but that venture capital is really only meant for software, and individual products that have a clear path towards being the company being 20x the size in like 5 to 10 years, which is not the reality for a lot of these companies.

And so there is this space where it’s somewhere in between a pure market return and pure government philanthropy, where in theory impact investing lives. If you really dig under someone who's calling themselves impact investing, and they either are a lot more like philanthropy or a lot more like market rate returns, like they're not actually offering something that's really in between there. That's a big challenge for a lot of our innovators, with even the most brilliant ideas. They get to folks in government and are like, “Come back to me when you've done this with 200 homes” and they're like, “But how do I get from 10 to 200. There’s no path to do that. There’s no one who will give me money to do that.”

So that's a big challenge we see. There are people who are really working on that and a lot of really smart people. I think there's going to be a lot more money, especially flowing to things that are addressing climate change goals that may be able to try and fill that gap and move forward.

One place for hope. So one would be, I think the most obvious, I think about it that I'm sure this is true for you, Jenna, but just that I love my job because of the innovators that we get to support. They’re amazing. They're people who see a challenge and then see a solution they just created out of their minds, and then they build an organization behind it. And these people are so inspiring, and they're talking about stuff that may be problems that people don't even see, and they've already created a solution to that.

Like, I think The Kelsey is a great example, and a lot of people here in the Bay Area may be familiar with them, but Micaela and Caroline over at the Kelsey, who are really trying to chart forward a new design standard around people for housing with people with disabilities, and they've built this organization around it, where they've learned from developing, and they're raising funding and they have advocacy, and they just see a vision and opportunity where a lot of people don't. I just love that part of our work and gives me help every day to continue to show up and continue to want to support these types of people and support them towards scale.

And I only had a chance to talk about a couple of the ventures that were related to the topics that we’ve supported over the year that are related to topics that we’ve talked about today. But we’ve supported 22 organizations. We are announcing the next 5 that we’ll support over the summer. A lot of them are already working in California, a lot of them could work here in California, for those that are based here. If you want to learn more about being inspired by the work that’s possible, I really encourage you to go to our website and go to Housing Venture Lab and go to our cohorts, we actually have a video on each of them where you can learn more about their work.

And then the second would be this, and I already talked about this, but on the industrial policy place. No matter where the government goes in the in the next six months, I think there is a building consensus at the federal level for policy that supports US industry, and I think that's a really good opportunity for the housing industry writ large, whether it's addressing climate goals or thinking about building housing at a different scale.

I think sometimes we can feel hopeless because there's so many challenges we can't solve, and the challenges keep getting worse. But I'm optimistic that there may be ways to address larger pools of capital to address our housing challenges in the future?

Alex Schafran: Big support for the idea of housing as industrial policy for a whole slew of reasons, one of which, this is the other reason why I like talking about housing as an innovation. There’s a tendency for housers, especially folks who are involved in policy and politics, to forget that housing is an industry. Millions and millions of humans get up every morning and work in the housing industry. Very few of them actually do policy, and we forget that too often.

I think we often look and this is something that you know, I've had conversations with many of my pro housing friends and trying to convince all of the leaders of the pro housing organizations of this, that to be pro housing means to advocate for change and transformation of the industry, the nonprofit part of the industry, the for profit part of the industry, the finance part of the industry, the building part of the industry, the labor part of the industry: all of it.

That's really, I think, how we get to some of these housing solutions. And that's, again, one of the reasons why I don't think in there, you know, you all just been running innovation shops that were only doing startups. I wouldn't have been as excited to have you both here, and I think that's one of the things that's really exciting is, as I said earlier, is both of your organizations are really making an effort to both focus on industry and see housing as an industry, but to be broad in your approach.

Thank you both so much for being here. Just really excited to have you great to hear mention of The Kelsey. I'm hoping that we'll have The Kelsey on at some point, talk about the full range of supportive housing. I just want to mention another area of innovation that I think both of you all have supported in various ways, organizations like Frolic, who are working on innovations in housing tenure. It's super important, right? That's a major area of innovation. There's a lot of ways where we can do multifamily homeownership, different ways of owning property, and that is a technology that is an innovation, it's a policy innovation, it's a financing innovation, it's all of those things, and our system doesn't currently support it in the way that it can.

Thank you to my fellow fruit tree lover, Michelle Boyd, for being here. Thank you to my fellow Marinite, Jenna Louie, for being here. And I'm really happy that both of you are in California. We are definitely the better of it. And thank you for listening.

Michelle Boyd also was a Housing After Dark listener, before she became a Housing After Dark guest, that's a lesson to all of you. There are other listeners that are already coming on. And if you want to be a guest and you are a listener, the best way is to just tell me that you listen and you never know.

Michelle Boyd: I got in touch with Alex by emailing him cold after reading the podcast transcript. So yeah, it’s an encouragement to the audience.

Alex Schafran: Thank you very much to both of you.

Share this post